Phison, Garden of Anticipations/ London

Phison, Garden of Anticipations

Oil on canvas, 160 × 120 cm

Private collection, London

"Phison is the eye of God, seeing itself in a world not yet born."

The first act of self-observation of the Whole.

I was interested in how long I could sustain a form of pre eternity not in terms of chaos but as the simultaneous presence of already named principles. This was a direct challenge for my psyche.

My entire being tends to define itself through act, gesture, metamorphosis and irreversibility, to remain at the centre of the event rather than in its potential. Here I deliberately shift my direction and explore pre form through potentials, pre dual yet aligned with the vector of Paradise.

I wanted to understand what it means to create a harmony of earth at the source of Phison, before world, before law, before aggression and narrative, before hunger and domestication.It was an attempt to hold a pre dramatic psychic form.

Pre Arcadia rather than mappae mundi, a harmony of all potentials before any ordering of the world.

A world without object and without lack. An objectless eros. Conditions under which a world might arise.

Shame and disgust opened the entry into the investigation of Paradise.

Shame and disgust. From Fra Angelico to proto affect.

It began when Fra Angelico’s Mocking of Christ struck me as an event.

A work of devotio, refined and restrained, painted for a monastic cell. In the Gospels the executioners play at prophecy and say "prophesy who struck thee". He writes an instruction on how to bear affect in the kinetic language of Mary and Dominic. Non subjective evil appears as dissociated hands. This is the San Marco fresco of about 1440 to 1442.

Reflections on the purity of affect, on non resistance without capitulation understood as an instrument of power, on the force of non response, on silence as a method of exaltation, on the absolute aperformative empathy of Mary and on Dominic’s perspectiva artificialis brought me back to Melanie Klein and the question of proto affect.

I returned to disgust and envy as charged potentials of future affects, to proto feeling that will later condense into what we call libido.

At the same time I began to see the closed ecology of evil in a new way, as a system that requires a turbine of duality.

I also became interested in the fine differentiation of impulses and appearances in Dante’s Paradise, which Alexander Filonenko reads with exceptional clarity.

The first experiment was a self portrait in oil which I painted in a manner I would normally never adopt. Salon softness and tasteful correctness became the perfect resistance to work against.

Conditions of the commission and a personal crisis.

This painting cannot be separated from its context.

There was a personal crisis and there were commissioners who created no resistance to any form. They behaved like unconditionally loving parents. They invited me into their lives on a quasi shamanic ground, with irony and openness, offering an artist of a predominantly thanatic register the possibility of moving towards a clearer engagement with fertility.

This alone was enough for the large erotic charge of my psyche to collapse without its usual mortido support.

I decided to test an anthropological hypothesis.

Can libidinality exist in a pre active world, before lack and before aggression. What if satiety is the fundamental form.

What if the key to first hunger is a dialogical window at the threshold of otherness.

A remark

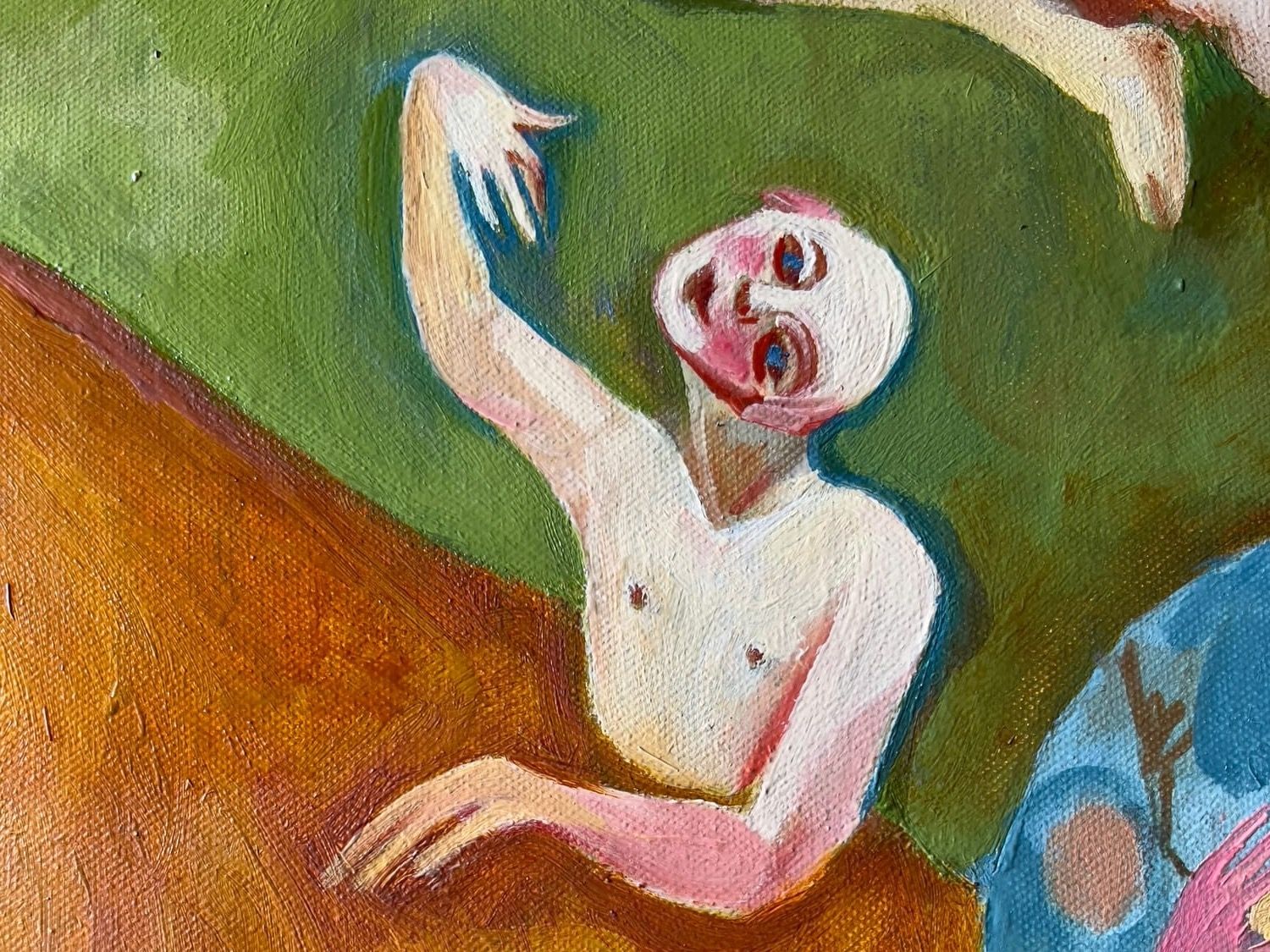

To put it plainly. For the first time I set myself the task of making a large work where no one has sex, no one kills or eats anyone and no one is metamorphosing while moving. At the same time I could not escape into hermaphroditism.

All figures had to be honestly divided into female and male bodies. This was perhaps the most difficult part. To sustain binary bodies inside a pre dual world.In parallel I was almost losing my mind from the amount of pure colour.

The underpainting was halftone and hesitant.

The later purity of colour challenged my own distrust of harmony.

Libidinal field.

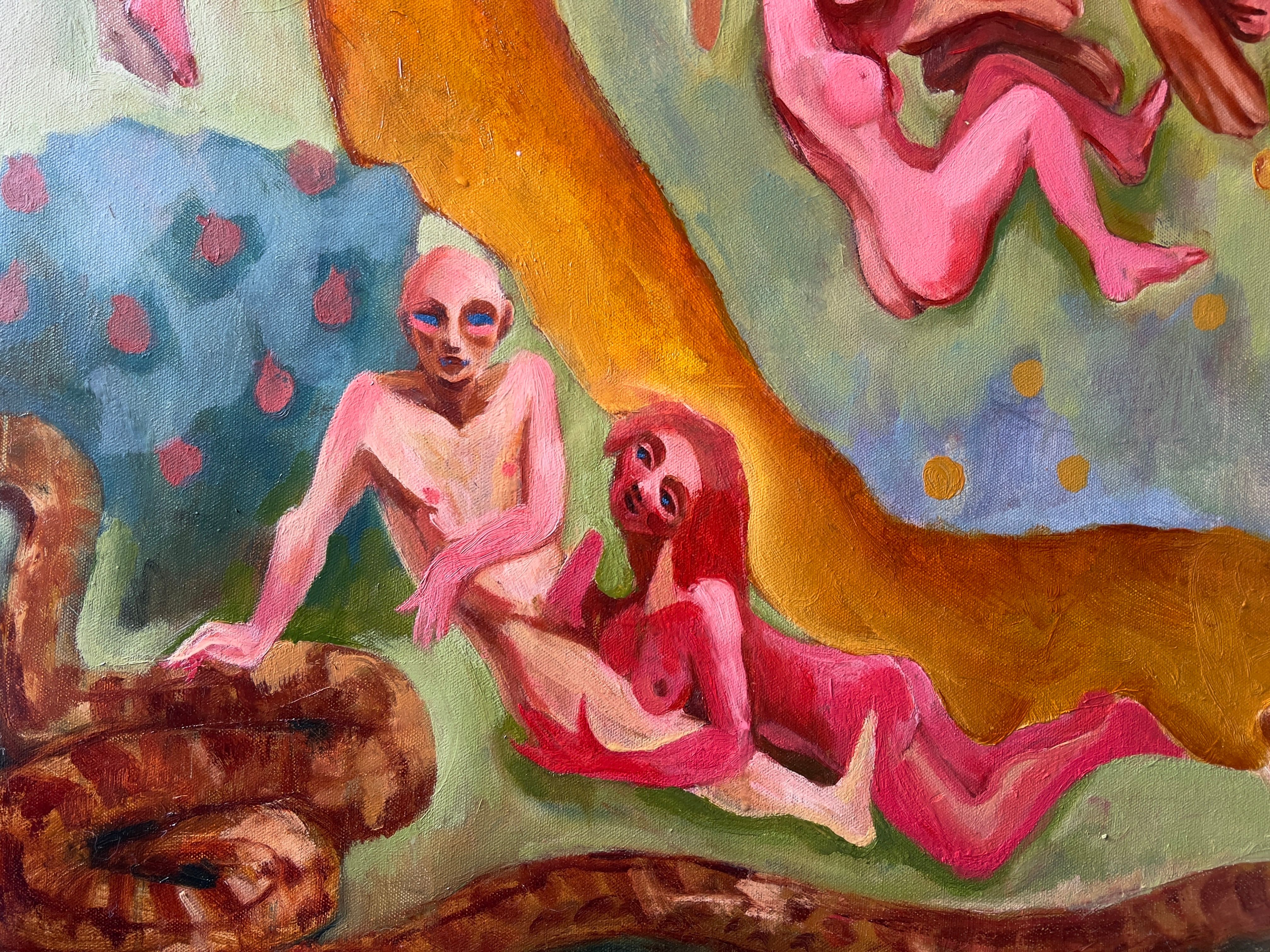

The painting opens with a tiger chimera and the shadow of a non shepherd, a figure of recognition.

The tiger, having seen the fiery flower, bears witness to the origin of Phison. Three goat heads appear as three channels of sensation, split vision, hearing and attention.

This is the birth of the gift of the senses.

Fra Angelico remains in the background as someone who sees passion with Dominic’s structured gaze and with Mary’s inclined heart. Unlike classical perspectiva artificialis with its single cone of vision, perception here is already split. It is significant that it was a goat that appeared. In the flow of the unconscious I often shape forms almost automatically.

My earlier explorations of pre aggression usually came through lions feeding from a hind and all of this remained inside the poles and dual categories.

The composition answers the question of why the goat. A sheep would have brought anxiety. A hind would have introduced fragility and reactivity. A foal would have implied movement.

Zoobiological mythopoesis. The goat.

The goat inhabits a zero zone of aggression and panic. Biologically it is an animal with a low fear response and with soft, non hierarchical sociality. Goats do not look with a focused tunnel gaze but with an open arc of attention. Their horizontal pupils and laterally placed eyes provide a visual field of about 280 to 340 degrees, one of the widest among mammals. They can track the left, the right and the above almost simultaneously.

Goats are social yet lack rigid territorial structure. They live in loose groups connected without a hard vertical. This is a proto social form without hierarchy. Each individual is oriented inward while the heightened sensitivity of one becomes a homeostatic background for the group. Ethologists refer to this as affective field transmission, the spread of affective state without language and without authority.

In early Christian and gnostic texts such as the Pseudo Clementine Homilies and Origen’s Contra Celsum there are descriptions of multi faced beings of observation.

These are not goats but the structure of multi faced perception is analogous.

In several ancient traditions the goat is indeed a sacrificial animal, but in the Iranian Zoroastrian context its role is less central than that of the bull. For me the goat is not a victim but an organ of perception in a world that has not yet developed fear or hierarchy.

Reduced predators.

White tigers in the painting remain in a state of resting vigilance. Genetically their whiteness results from a mutation in the gene SLC45A2 which reduces pigment. Such animals camouflage less effectively yet discriminate contrast more clearly and shift their strategy away from hunting towards observation.

Studies show altered social behaviour, greater attention to environment and slower decision making. In India white tigers were seen as children of Devi, manifestations of light in the form of a predator.

In East Asian cosmography the White Tiger of the West belongs to the four elemental guardians.

Here the white tiger is a predator without a hunt, an organ of recognition rather than violence. It finds the scarlet proto flower because it is attuned to such anomalies.

A little botany. Fig, wasp and regeneration.

I painted fig and mulberry trees, Iranian shrubs and in the final stages a pomegranate tree beside the entrails of the anaconda.

I love the fig as a whole and every part of the tree offers a dense biological and olfactory map.

(Usually I devote myself to bees and to their honey plants.) In this pre world the pair that arrives is different.

Fig and fig wasp. This is one of the classic ancient mutualisms, a primary system of mutual recognition. The fig has high regenerative capacity. When injured it produces a fragrant latex, a mix of rubber, resins, enzymes and antimicrobial compounds. Fig trees also generate adventitious roots and can root from trunk fissures, broken branches or fallen bark. In this sense it is a phoenix tree.

Thousands of epicormic buds lie dormant along the trunk and activate after extreme stress.

Hence the phenomenon of sacred fig groves which genetic analysis sometimes reveals as a single clonal organism.

In several gnostic texts such as those from Nag Hammadi the fig is the first plant that recognises the human and in doing so opens the cycle of knowledge.

The direction is important. The plant recognises the human.

The wasp, the inverted garden and the needle’s eye.

Here form corresponds to form rather than to aggression or competition. Each fig species has its own wasp species and each wasp its fig. This is an ancient co evolutionary system around seventy to ninety million years old.

The sycomore is an inverted garden. What we see as a fruit is an inward folded inflorescence. Eating a fig means eating a sealed garden organ.

The pollinating wasp carrying pollen of its cradle tree enters through the ostiole which is so narrow it leaves its wings behind. This gesture looks like a one way sacrifice but biologically it is the closing of a cycle. The fig distinguishes young flowers for larvae from mature ones for seed and regulates larval development hormonally. The new generation of wasps emerges already carrying pollen. Males open an exit. Females fly out, take pollen and find only their fig species.

The system functions only in this exact specificity. It is a genetically encoded mutual recognition. The fig recognises the wasp and the wasp recognises the odour and form of the ostiole.

This is a primordial form of coupling that precedes symbolism, sexuality and language.

Flowers. Two entrances into form.

The painting contains two flowers and the figs. The golden magnolia is my naive reconstruction of an archeo flower, an early angiosperm line.

Magnolias belong to ancient branches and palaeobotany reconstructs them as warm ochre flowers with thick waxy texture and beetle pollination. It reflects the forms of Phison and invites contemplation by the naive or holy fool who must grow into understanding.

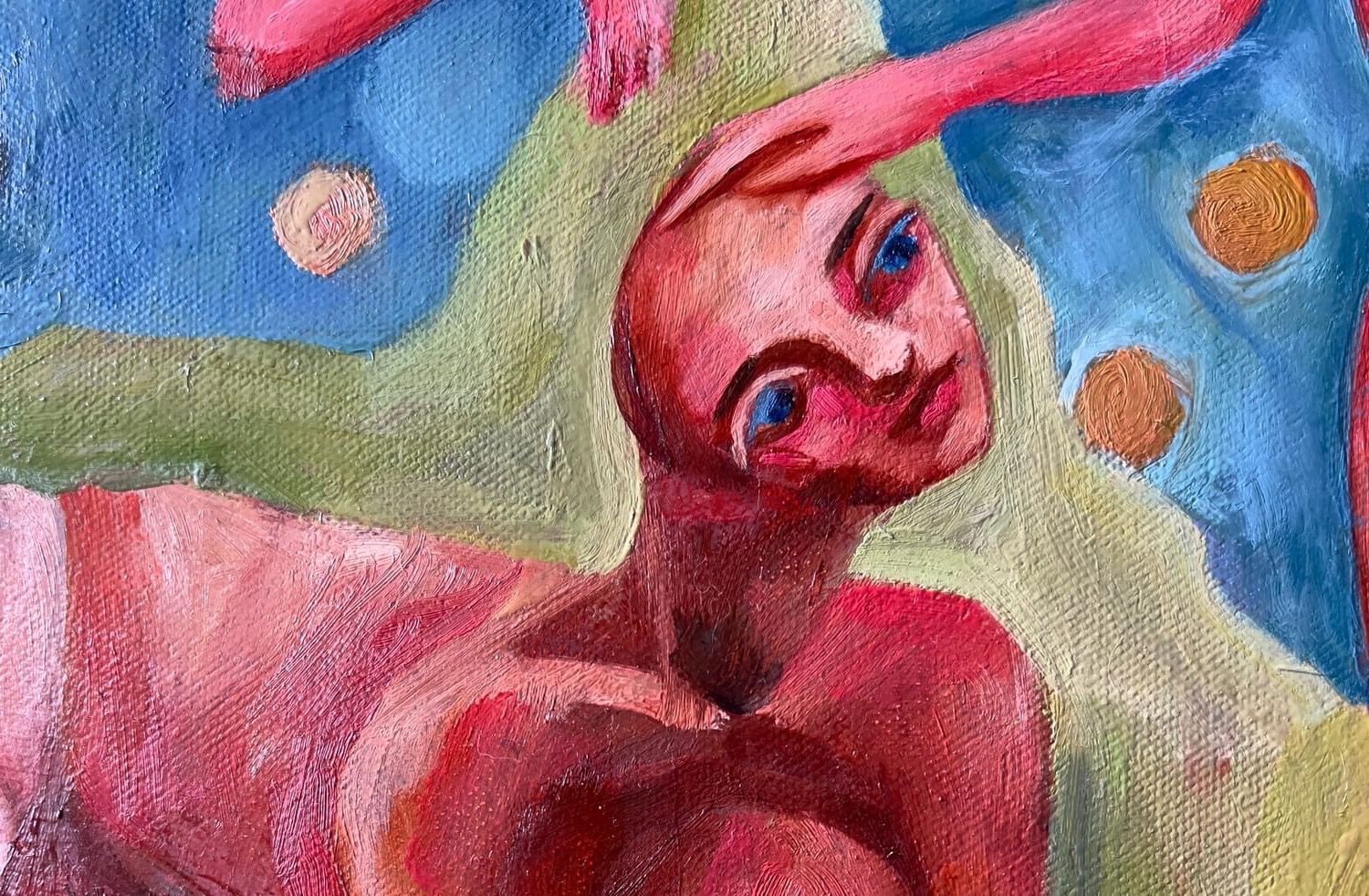

The scarlet flower is an anthocyan proto blossom. A hypothetical signal of the object world. It signals to early pollinators such as beetles and early warm blooded creatures. The white tiger is particularly sensitive to contrast and its visual behaviour can be described as pattern anomaly fixation. It sees the anthocyan flare as an early warm blooded organism might have seen the first flowering of the world.

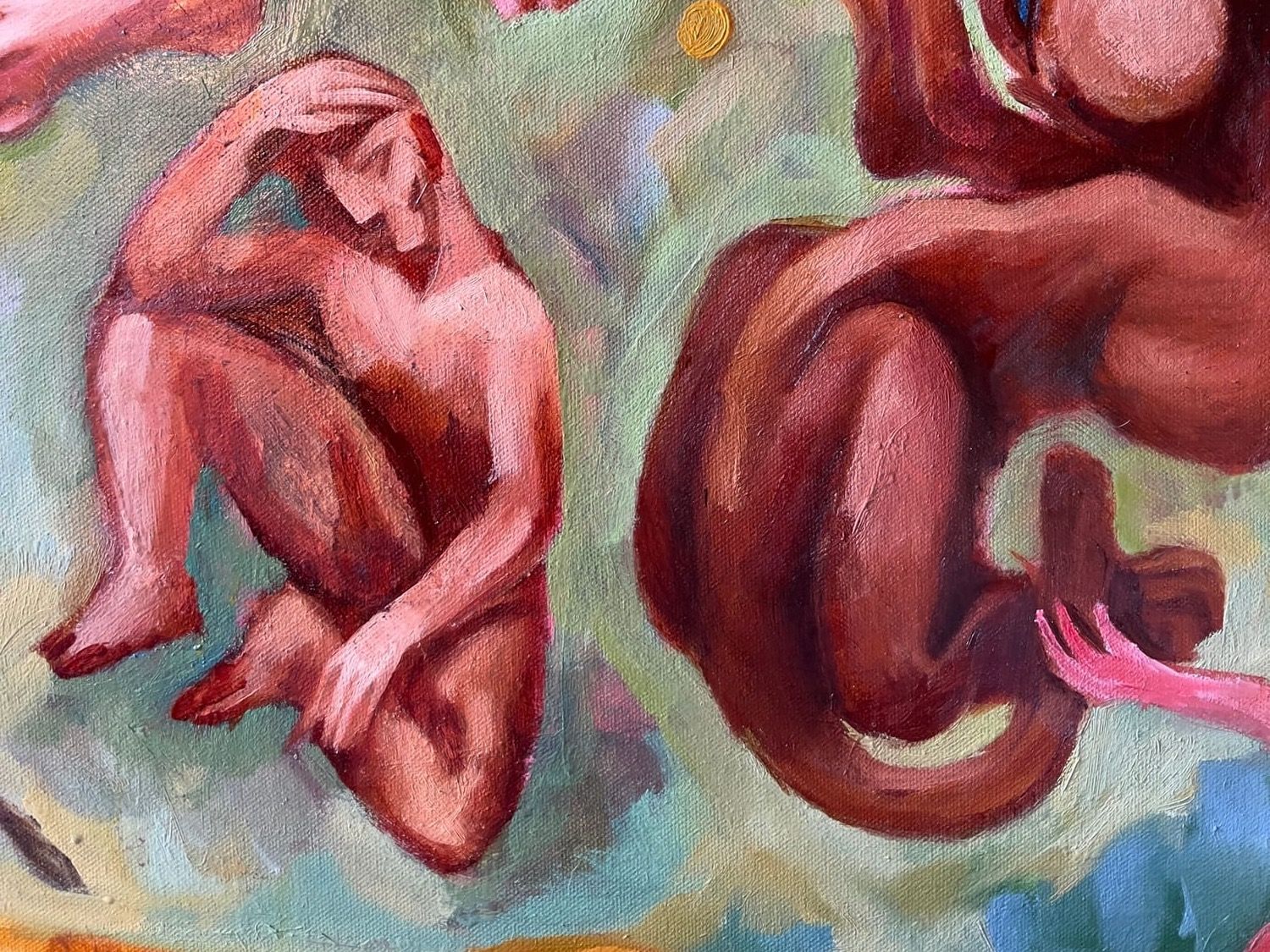

Posturality

In the main groupings human figures drift towards animals as sources of heat rather than as social agents. This is pre social and pre linguistic corporeality. The upper right register contains verticals.

First signs of agency, a proto rider and the proto fetishisation of the foot, a pre ritual. The figure with raised arms appears as a petroglyphic extasis and recognises the external world as source. The sphere condensed over Phison is not a sun but a densification of the same matter that flows from the river.

Thermo haematological colour. An anatomy of pre-desire.

Another way to strain the canvas biologically is to work with colour as physiology rather than emotion, with a conscious appeal to the amniotic memory of the body.

The anthocyan register is a dermatological language of excitation, the colour of the first vascular response to affect.

Libidinality is moved into gold and pure colour. Energy is shifted from red into gold.

Ochre is the colour of liver, kidney, mucosa, lymphatic tissue and placenta. It is not earth but internal matter, the structural flesh of the world.

The gold of Phison is the space of libido and the single source of light. It is non generative and non centred, a diffuse substance of the river.

Pre narrative scenes before law and before choice.

A pre Oedipal landscape appears as a set of conditions, a world of objectless eros on the threshold of event.

The donkey and the Aeon child.

The donkey entered the painting from Zoltan and strongly shaped the composition of the right bank.

In Jacobus de Voragine’s Golden Legend the donkey is the animal that recognises the Divine before the human.

In Syro Chaldaean and Coptic traditions it is the creature that hears angelic speech.

There are two points of recognition in the painting. The entry point which is the fiery flower. The exit point which is first hunger, the donkey.

The donkey guides the movement into subjectivity.

This is the realm in which division begins. Death, hunger, dyad, love, aggression. All other beings remain inside the garden. The donkey enters negotiations with God before the first touch of real hunger.

It holds the rhythm and the knowledge, listens and decides when history begins.

Once it answers the garden is no longer closed.

The viewer following it tastes sycomore as in Giotto’s Entry into Jerusalem where the passage into the city and into the narrative occurs through the animal.

Olfactory map.

A direct route into the limbic system

The intention is to bypass metaphor and cultural nuance and to move directly into the limbic system.

The base is a heavy and almost silent reptilian musk.

Wet clay, silt, vetiver and geosmin.

The fig groves provide what I love in this motif, a plant with an animal overtone. Milk, coconut, smoke, cat litter, ancient earth.The heart is skin, fat and warm sweat without individuality in the spectrum of Iso E.

A trace of cat urine and coumarin forming a dry, powdery line. Aldehydes clean and abstract the animality.

The living presence belongs to the plants. Iris becomes a dry interpretation of a clean young goat held by a nameless pre pubertal child.

This is strengthened with opoponax, myrrh and the ozone of Phison along with ambergris, salt and cashmeran.

The flowers appear through saffron and magnolia.

A fine, fresh indole with a slight mentholated breath forms the floral and lucid part of the composition.

For Yanochka and Zoltan to whom this belongs.

Special thanks to Alex and Oleg

Melanie Klein, Envy and Gratitude and Other Works 1946–1963, The Hogarth Press, 1975

Melanie Klein, The Psycho-Analysis of Children, The Hogarth Press, 1932

Hanna Segal, Introduction to the Work of Melanie Klein, The Hogarth Press, 1964

Jean Laplanche, Life and Death in Psychoanalysis, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1976

Julia Kristeva, Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection, Columbia University Press, 1982Origen, Contra Celsum, Cambridge University Press, 1953

The Pseudo-Clementine Homilies, edited and translated by A. Smith Lewis

The Nag Hammadi Scriptures, edited by Marvin Meyer, HarperOne, 2007

Dante Alighieri, La Divina Commedia: ParadisoMary Boyce, Zoroastrians: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices, Routledge, 1979

B. T. Anklesaria, Zand-Ākāsīh: Iranian or Greater Bundahišn, Bombay, 1956

Jean Kellens, Essays on Zarathustra and Zoroastrianism, Istituto Italiano per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente, 2000James M. Cook and Jean-Yves Rasplus, Mutualists with Attitude: Coevolving Fig Wasps and Figs, Trends in Ecology and Evolution, 2003

E. Allen Herre et al., The Evolution of Fig–Wasp Mutualisms, Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden, 2006

George D. Weiblen, How to Be a Fig Wasp, Annual Review of Entomology, 2002

C. C. Berg and E. J. H. Corner, Moraceae — Ficus, Flora Malesiana, Leiden, 2005Jose R. Obeso, The Costs of Reproduction in Plants, New Phytologist, 2002

Navjot Kaur and Bhupinder Singh, Adventitious Rooting in Ficus Species, Journal of Plant Physiology

Else Marie Friis, Peter R. Crane and Kaj Raunsgaard Pedersen, Early Flowers and Angiosperm Evolution, Cambridge University Press, 2011

Hervé Sauquet et al., The Ancestral Flower of Angiosperms and its Early Diversification, Nature Communications, 2017Xu X. et al., The Genetic Basis of White Tigers, Current Biology, 2013Monica Battini et al., Hair Coat Condition in Dairy Goats, Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 2013

G. C. Miranda-de la Lama et al., Animal Welfare in Goats, Small Ruminant Research, 2018Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Phenomenology of Perception, Routledge, 1962

Georges Didi-Huberman, Ce que nous voyons, ce qui nous regarde, Les Éditions de Minuit, 1992

Georges Bataille, L’Érotisme, Les Éditions de Minuit, 1957Rachel Herz, The Scent of Desire, HarperCollins, 2007

Constance Classen, David Howes and Anthony Synnott, Aroma: The Cultural History of Smell, Routledge, 1994

Luca Turin and Tania Sanchez, Perfumes: The Guide, Profile Books, 2008Fra Angelico, The Mocking of Christ, fresco, San Marco, Florence, c. 1440–1442

Giotto di Bondone, Entry into Jerusalem, Cappella degli Scrovegni, Padua, c. 1305

Hieronymus Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights, c. 1490–1505

Piero di Cosimo, The Discovery of Honey by Bacchus, c. 1499

Hildegard von Bingen, Scivias, illuminated manuscripts, c. 1151–1152